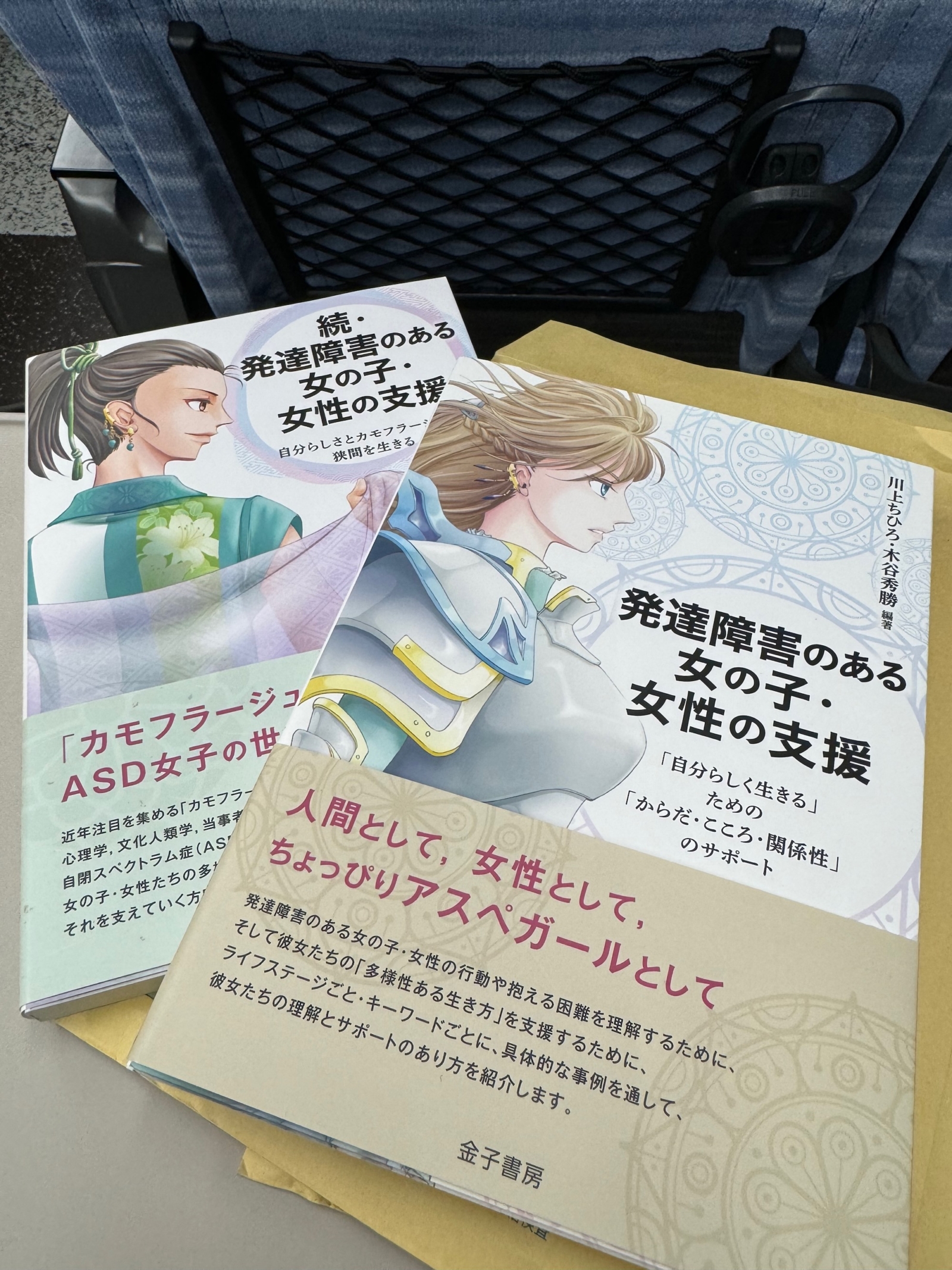

Some time ago, I was invited by Kohei Kato, an autism researcher at Tokyo Gakugei University who also works as an editorial manager at Japanese publisher Kaneko Shobo. He immediately told me not to expect too much, but he wanted to get acquainted. He gave me two books from his publishing company about autism in girls and women, in Japanese. I haven’t read the books yet (my Japanese isn’t that good, unfortunately), but the titles were promising – these books were about camouflage, or masking.

I always had the impression that knowledge about autism was somewhat behind in Japan, and maybe it still is, but the conversation with this man made me feel positive. I wanted to know more, so when he invited me to join Hobby Talk, the discussion group for autistic girls that he leads, I enlisted Olga (to interpret) and we headed to the university campus together.

Hobby Talk

Hobby Talk was held on the campus of a university near Kokubunji station. In the playroom, a room with a large mirror that very likely hides a room on the other side (like in police interrogations), there was a small table and some chairs. There were about eight girls, but some of them were students who were participating in the project as part of their studies. There was also a laptop on the table, because two girls were participating online due to various circumstances.

The purpose of Hobby Talk is twofold: on one hand, it provides an opportunity for autistic girls to enjoy social interaction without anyone telling them what they are doing wrong or how they can improve. “We are not here to learn how to communicate perfectly,” said the researcher. “We are here to have fun with communication.” On the other hand, it is an opportunity for the researchers and students to study autistic communication. What do we autistics do differently, and what impact does that have?

The structure of the afternoon was as follows: Everyone could talk about his or her hobby for three minutes (his or her hobby, because the group was for girls, but the researcher also participated). After that, the rest could ask questions for ten minutes. The time was kept, and there was really only one rule: You couldn’t say negative things about someone else’s hobby.

Polaroids and Pretty Cure

Since everyone was going to participate, Olga and I brought things as well. I chose a couple of Polaroid cameras: one that you can install special filters on, and an Instax that I recently bought, a special edition for the first anniversary of the Hayabusa Shinkansen. (The researcher was so fascinated by this that when I mentioned I also had a Polaroid i-Zone in the shape of a Romancecar train, he said I should bring that next time!) Olga decided to bring her seashell collection and spoke about her love for nature.

Two girls in the group had the same interest, so we ended up spending almost half an hour learning about the phenomenon of Pretty Cure. I had never heard of this anime before, and I still don’t understand much about it, but it certainly looks pretty.

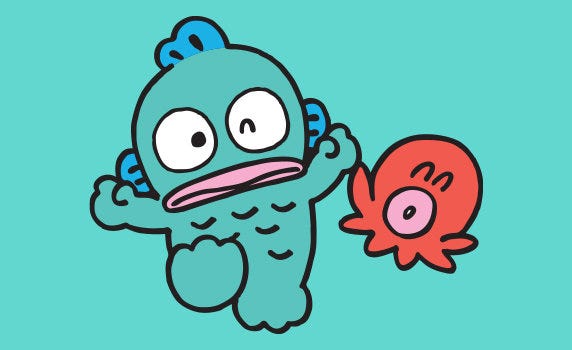

One girl had brought her collection of stuffed frogs, and another talked about her love for Hangyodon, a Sanrio character (like Hello Kitty) with the head of a fish and the body of a human. “A sort of reverse mermaid!” A shy girl initially said little about her cosplay adventures, but when we asked more questions, it turned out she had a lot of talent; the outfits she made herself and wore to conventions were stunning.

Although all the student researchers had introduced themselves to us beforehand, at some point we couldn’t be sure who the autistic individuals were and who the students were. Almost everyone asked questions, and the interactions seemed to flow smoothly. The hobbies didn’t really help to figure it out either – everyone had a unique hobby or collection!

I was quite exhausted afterward (partly due to the language difference, I think), but the non-autistic Olga was as well. In short: “But you don’t look autistic at all” seems to apply in Japan too.

Whoa, so oldschool! An RSS feed!

Save this link in your RSS reader and follow my blog however you want it – chronological, in your mailbox, in your browser... Yes, the past is here!

https://www.toeps.nl/blog-en/feed/